Plugins for OpenKAT: boefjes, whiskers and bits

OpenKAT is modular and can be easily extended. This guide provides a first step for the development of new plugins: boefjes that scan, whiskers that collect objects, and bits that contain businessrules.

OpenKAT comes with a KATalog of boefjes, which can be viewed through the front end of the system. The premise is that all information is processed and stored in the smallest unit, ensuring the modular nature of OpenKAT.

OpenKAT can access multiple KATalogs, so it is possible to create your own overview of boefjes in addition to the official KATalog. This is of interest to organizations that use boefjes for specific purposes or with software that has a different licensing model.

This guide explains how the plugins work and how they are created, and gives an overview of which plugins already exist. It also explains the configuration options available.

What types of plugins are available?

There are three types of plugins, deployed by OpenKAT to collect information, translate it into objects for the data model and then analyze it. Boefjes gather facts, Whiskers structure the information for the data model and Bits determine what you want to think about it; they are the business rules. Each action is cut into the smallest possible pieces.

Boefjes gather factual information, such as by calling an external scanning tool like nmap or using a database like Shodan.

Whiskers analyze the information and turn it into objects for the data model in Octopoes.

Bits contain the business rules that do the analysis on the objects.

Boefjes and Whiskers are linked together through the mime-type that the boefje passes along to the information. For each mime-type, multiple Boefjes and Whiskers are possible, each with its own specialization. Thus, the data from a boefje can be delivered to multiple whiskers to extract a different object each time. Bits are linked to objects and assess the objects in the data model. Some bits are configurable with a specific configuration stored in the graph.

How does it work?

A hostname given as an object to OpenKAT, for example, is used as input to a search by the matching boefjes. Based on the data model, logically related objects are searched to get a complete picture.

Thus, OpenKAT is like a snowball rolling through the network based on the data model. The logical connections between objects point the way, and OpenKAT keeps looking for new boefjes until the model is complete.

The new objects in the data model are evaluated by Bits, the business rules. This produces findings, which are added as objects. For example, the hostname includes a dns configuration, which must meet certain requirements. If it goes outside the established parameters it leads to a finding.

Where to start?

The first question is what information you need. If you know this, there are a number of options, which determine what is best to do:

the information is already present in the data model -> create a businessrule (bit)

the information is present in the output of an existing boefje -> create a normalizer (whiskers)

the information is not yet available -> create a boefje, modify the data model and create a normalizer

If you want to add factual information, use a boefje. Want to add an opinion or analysis, use a bit.

OpenKAT assumes that you collect and process all information in the smallest possible units so that they can contribute back to other combinations and results. This is how you maintain the modular nature of the package.

To make a finding about a CVE to a software version, you need multiple objects: the finding of the software, the version, the CVE. That combination then leads to the object of the finding.

Existing boefjes

The existing boefjes can be viewed via the KATalog in OpenKAT and are on GitHub in the boefjes repository.

Object-types, classes and objects.

When we talk about object-types, we mean things like IPAddressV4. These have corresponding Python classes that are all derived from the OOI base class. These classes are defined in the Octopoes models directory.

They are used everywhere, both in code and as strings in json definition files.

When we talk about objects, we usually mean instance of such a class, or a ‘record’ in the database.

Example: the boefje for shodan

The boefje calling Shodan gives a good first impression of its capabilities. The boefje includes the following files.

__init.py__, which remains empty

boefje.json, containing the normalizers and object-types in the data model

cover.jpg, with a matching cat picture for the KATalog

description.md, simple documentation of the boefje

main.py, the actual boefje

normalize.py, the normalizer (whiskers)

normalizer.json, which accepts and supplies the normalizer

requirements.txt, with the requirements for this boefje

schema.json, settings for the web interface formatted as JSON Schema

boefje.json

boefje.json is the definition of the boefje, with its position in the data model, the associated normalizer, the object-types and the findings that the combination of boefje and normalizer can deliver.

An example:

{

"id": "shodan",

"name": "Shodan",

"description": "Use Shodan to find open ports with vulnerabilities that are found on that port",

"consumes": [

"IPAddressV4",

"IPAddressV6"

],

"produces": [

"Finding",

"IPPort",

"CVEFindingType"

],

"scan_level": 1

}

The object-types associated with this boefje are IPAddressV4, IPAddressV6, Finding, CVEFindingType.

This boefje consumes IP addresses and produces findings about the open ports, supplemented by the information about these ports.

Using the template as a base, you can create a boefje.json for your own boefje. Just change the name and id to the name your boefje.

NOTE: If your boefje needs object-types that do not exist, you will need to create those. This will be described later in the document.

The boefje also uses variables from the web interface, like the Shodan the API key. There are more possibilities, you can be creative with this and let the end user bring settings from the web interface. Use environment variables or KATalogus settings for this. The schema.json file defines the metadata for these fields.

schema.json

To allow the user to pass information to a boefje runtime, add a schema.json file to the folder where your boefje is located. This can be used, for example, to add an API key that the script requires. It must conform to the https://json-schema.org/ standard, see for example the schema.json for Shodan:

{

"title": "Arguments",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"SHODAN_API": {

"title": "SHODAN_API",

"maxLength": 128,

"type": "string",

"description": "A Shodan API key (see https://developer.shodan.io/api/requirements)."

}

},

"required": [

"SHODAN_API"

]

}

This JSON defines which additional environment variables can be set for the boefje.

There are two ways to do this.

Firstly, using the Shodan schema as an example, you could set the BOEFJE_SHODAN_API environment variable in the boefje runtime.

Prepending the key with BOEFJE_ provides an extra safeguard.

Note that setting an environment variable means this configuration is applied to _all_ organisations.

Secondly, if you want to avoid setting environment variables or configure it for just one organisation,

it is also possible to set the API key through the KAT-alogus.

Navigate to the boefje detail page of Shodan to find the schema as a form.

These values take precedence over the environment variables.

This is also a way to test whether the schema is properly understood for your boefje.

If encryption has been set up for the KATalogus, all keys provided through this form are stored encrypted in the database.

Although the Shodan boefje defines an API key, the schema could contain anything your boefje needs. However, OpenKAT currently only officially supports “string” and “integer” properties that are one level deep. Because keys may be passed through environment variables, schema validation does not happen right away when settings are added or boefjes enabled. Schema validation happens right before spawning a boefje, meaning your tasks will fail if is missing a required variable.

main.py

The boefje itself imports the shodan api module, assigns an IP address to it and accepts the output. This output goes to Bytes and is analyzed by one (or more) normalizers. The link between the normalizer and the byte is made via the mime-type, which you can give in the set function in the byte. The code block below also contains a check, to prevent you from asking for non-public IP addresses.

import json

import logging

from typing import Tuple, Union, List

import shodan

from os import getenv

from ipaddress import ip_address

from boefjes.job_models import BoefjeMeta

def run(boefje_meta: BoefjeMeta) -> List[Tuple[set, Union[bytes, str]]]:

api = shodan.Shodan(getenv("SHODAN_API"))

input_ = boefje_meta.arguments["input"]

ip = input_["address"]

results = {}

if ip_address(ip).is_private:

logging.info("Private IP requested, I will not forward this to Shodan.")

else:

try:

results = api.host(ip)

except shodan.APIError as e:

if e.args[0] != "No information available for that IP.":

raise

logging.info(e)

return [(set(), json.dumps(results))]

Normalizers

The normalizer imports the raw information, extracts the objects from it and gives them to Octopoes. They consist of the following files:

__init__.py

normalize.py

normalizer.json

normalizer.json

The normalizers translate the output of a boefje into objects that fit the data model. Each normalizer defines what input it accepts and what object-types it provides. In the case of the Shodan normalizer, it involves the entire output of the Shodan boefje (created based on IP address), where findings and ports come out. The normalizer.json defines these:

{

"id": "kat_shodan_normalize",

"consumes": [

"shodan"

],

"produces": [

"Finding",

"IPPort",

"CVEFindingType"

]

}

normalize.py

The file normalize.py contains the actual normalizer: Its only job is to parse raw data and create, fill and yield the actual objects. (of valid object-types that are subclassed from OOI like IPPort)

import json

from typing import Iterable

from octopoes.models import OOI, Reference

from octopoes.models.ooi.findings import CVEFindingType, Finding

from octopoes.models.ooi.network import IPPort, Protocol, PortState

from boefjes.job_models import NormalizerOutput

def run(input_ooi: dict, raw: bytes) -> Iterable[NormalizerOutput]:

results = json.loads(raw)

ooi = Reference.from_str(input_ooi["primary_key"])

for scan in results["data"]:

port_nr = scan["port"]

transport = scan["transport"]

ip_port = IPPort(

address=ooi,

protocol=Protocol(transport),

port=int(port_nr),

state=PortState("open"),

)

yield ip_port

if "vulns" in scan:

for cve in scan["vulns"].keys():

ft = CVEFindingType(id=cve)

f = Finding(finding_type=ft.reference, ooi=ip_port.reference)

yield ft

yield f

Yielding a DeclaredScanProfile

Additionally, normalizers can yield a DeclaredScanProfile.

This is useful if you want to avoid the manual work of raising these levels through the interface for new objects.

Perhaps you have a trusted source of IP addresses and hostnames you are allowed to scan intrusively.

Or perhaps you do not have intrusive boefjes enabled and always want to perform a DNS scan on new IP addresses.

As an example, see these lines in kat_external_db/normalize.py:

def run(input_ooi: dict, raw: bytes) -> Iterable[NormalizerOutput]:

...

yield ip_address

yield DeclaredScanProfile(reference=ip_address.reference, level=3)

This indicates that the ip_address should automatically be assigned a declared scan profile of level 3.

The safeguard here is that you always need to specify which normalizers are allowed to add these scan profiles.

This must be done through the SCAN_PROFILE_WHITELIST environment variable, which is a json-encoded mapping

of normalizer ids to the maximum scan level they are allowed to set.

An example value would be SCAN_PROFILE_WHITELIST='{"kat_external_db_normalize": 2}'.

When a higher level has been yielded, it will be lowered to the maximum. Combining the code and whitelist above would therefore be equivalent to combining this code with the whitelist:

def run(input_ooi: dict, raw: bytes) -> Iterable[NormalizerOutput]:

...

yield ip_address

yield DeclaredScanProfile(reference=ip_address.reference, level=2)

Of course, when the normalizer id is not present in the whitelist, the yielded scan profiles are ignored.

Adding object-types

If you want to add an object-type, you need to know with which other object-types there is a logical relationship. An object-type is as simple as possible. As a result, a seemingly simple query sometimes explodes into a whole tree of objects.

Adding object-types to the data model requires an addition in octopus. Here, an object-type can be added if it is connected to other object-types. Visually this is well understood using the Graph explorer. The actual code is in the Octopoes repo.

As with the boefje for Shodan, here we again use the example from the functional documentation. A description of an object-type in the data model, in this case an IPPort, looks like this:

class IPPort(OOI):

object_type: Literal["IPPort"] = "IPPort"

address: Reference = ReferenceField(IPAddress, max_issue_scan_level=0, max_inherit_scan_level=4)

protocol: Protocol

port: conint(gt=0, lt=2 ** 16)

state: Optional[PortState]

_natural_key_attrs = ["address", "protocol", "port"]

_reverse_relation_names = {"address": "ports"}

_information_value = ["protocol", "port"]

Here it is defined that to an IPPort belongs an IPAddress, a Protocol and a PortState.

It also specifies how scan levels flow through this object-type and specifies the attributes that format the primary/natural key: “_natural_key_attrs = [“address”, “protocol”, “port”]”.

More explanation about scan levels / indemnities follows later in this document.

The PortState is defined separately. This can be done for information that has a very specific nature so you can describe it.

class PortState(Enum):

OPEN = "open"

CLOSED = "closed"

FILTERED = "filtered"

UNFILTERED = "unfiltered"

OPEN_FILTERED = "open|filtered"

CLOSED_FILTERED = "closed|filtered"

Bits: businessrules

Bits are businessrules that assess objects. Which ports are allowed to be open, which are not, which software version is acceptable, which is not. Does a system as a whole meet a set of requirements associated with a particular certification or not? Some bits are configurable through a specific ‘question object’, which is explained below.

In the hostname example, that provides an IP address, and based on the IP address, we look at which ports are open. These include some ports that should be open because certain software is running and ports that should be closed because they are not used from a security or configuration standpoint.

The example below comes from the functional documentation and discusses the Bit for the IPPort object. The bit used for the analysis of open ports consists of three files:

__init.py__, an empty file

bit.py, which defines the structure

port_classification.py, which contains the business rules

Bit.py gives the structure of the bit, containing the input and the businessrules against which it is tested. An example is included below. The bit consumes input objects of type IPPort:

from bits.definitions import BitParameterDefinition, BitDefinition

from octopoes.models.ooi.network import IPPort, IPAddress

BIT = BitDefinition(

id="port-classification",

consumes=IPPort,

parameters=[],

module="bits.port_classification.port_classification",

)

The businessrules are contained in the module port_classification, in the file port_classification.py. This bit grabs the IPPort object and supplies the KATFindingType and Finding objects. The businessrules in this case distinguish three types of ports: the COMMON_TCP_PORTS that may be open, SA_PORTS that are for management purposes and should be closed, and DB_PORTS that indicate the presence of certain databases and should be closed.

The specification for a bit is broad, but limited by the data model: Whereas Boefjes are actively gathering information externally, bits only look at the existing objects they receive from Octopus. Analysis of the information can then be used to create new objects, such as the KATFindingTypes which in turn correspond to a set of specific reports in OpenKAT.

from typing import List, Iterator

from octopoes.models import OOI

from octopoes.models.ooi.findings import KATFindingType, Finding

from octopoes.models.ooi.network import IPPort

COMMON_TCP_PORTS = [25, 53, 110, 143, 993, 995, 80, 443]

SA_PORTS = [21, 22, 23, 3389, 5900]

DB_PORTS = [1433, 1434, 3050, 3306, 5432]

def run(

input_ooi: IPPort,

additional_oois: List,

) -> Iterator[OOI]:

port = input_ooi.port

if port in SA_PORTS:

open_sa_port = KATFindingType(id="KAT-OPEN-SYSADMIN-PORT")

yield open_sa_port

yield Finding(

finding_type=open_sa_port.reference,

ooi=input_ooi.reference,

description=f"Port {port} is a system administrator port and should not be open.",

)

if port in DB_PORTS:

ft = KATFindingType(id="KAT-OPEN-DATABASE-PORT")

yield ft

yield Finding(

finding_type=ft.reference,

ooi=input_ooi.reference,

description=f"Port {port} is a database port and should not be open.",

)

if port not in COMMON_TCP_PORTS and port not in SA_PORTS and port not in DB_PORTS:

kat = KATFindingType(id="KAT-UNCOMMON-OPEN-PORT")

yield kat

yield Finding(

finding_type=kat.reference,

ooi=input_ooi.reference,

description=f"Port {port} is not a common port and should possibly not be open.",

)

Bits can recognize patterns and derive new objects from them.

For example: The Bit for internet.nl can thus deduce from a series of objects whether a particular site meets the requirements of internet.nl or not. This bit retrieves findings from a series of items and draws conclusions based on them. The analysis underlying this is built up from small steps, which go around OpenKAT several times before enough information is available to draw the right conclusions:

from bits.definitions import BitParameterDefinition, BitDefinition

from octopoes.models.ooi.dns.zone import Hostname

from octopoes.models.ooi.findings import Finding

from octopoes.models.ooi.web import Website

BIT = BitDefinition(

id="internet-nl",

consumes=Hostname,

parameters=[

BitParameterDefinition(ooi_type=Finding, relation_path="ooi"), # findings on hostnames

BitParameterDefinition(ooi_type=Finding, relation_path="ooi.website.hostname"), # findings on resources

BitParameterDefinition(ooi_type=Finding, relation_path="ooi.resource.website.hostname"), # findings on headers

BitParameterDefinition(ooi_type=Finding, relation_path="ooi.hostname"), # findings on websites

BitParameterDefinition(ooi_type=Finding, relation_path="ooi.netloc"), # findings on weburls

BitParameterDefinition(ooi_type=Website, relation_path="hostname"), # only websites have to comply

],

module="bits.internetnl.internetnl",

)

Configurable bits

As policy differs per organization or situation, certain bits can be configured through the webinterface of OpenKAT. Currently the interface is quite rough, but it provides the framework for future development in this direction.

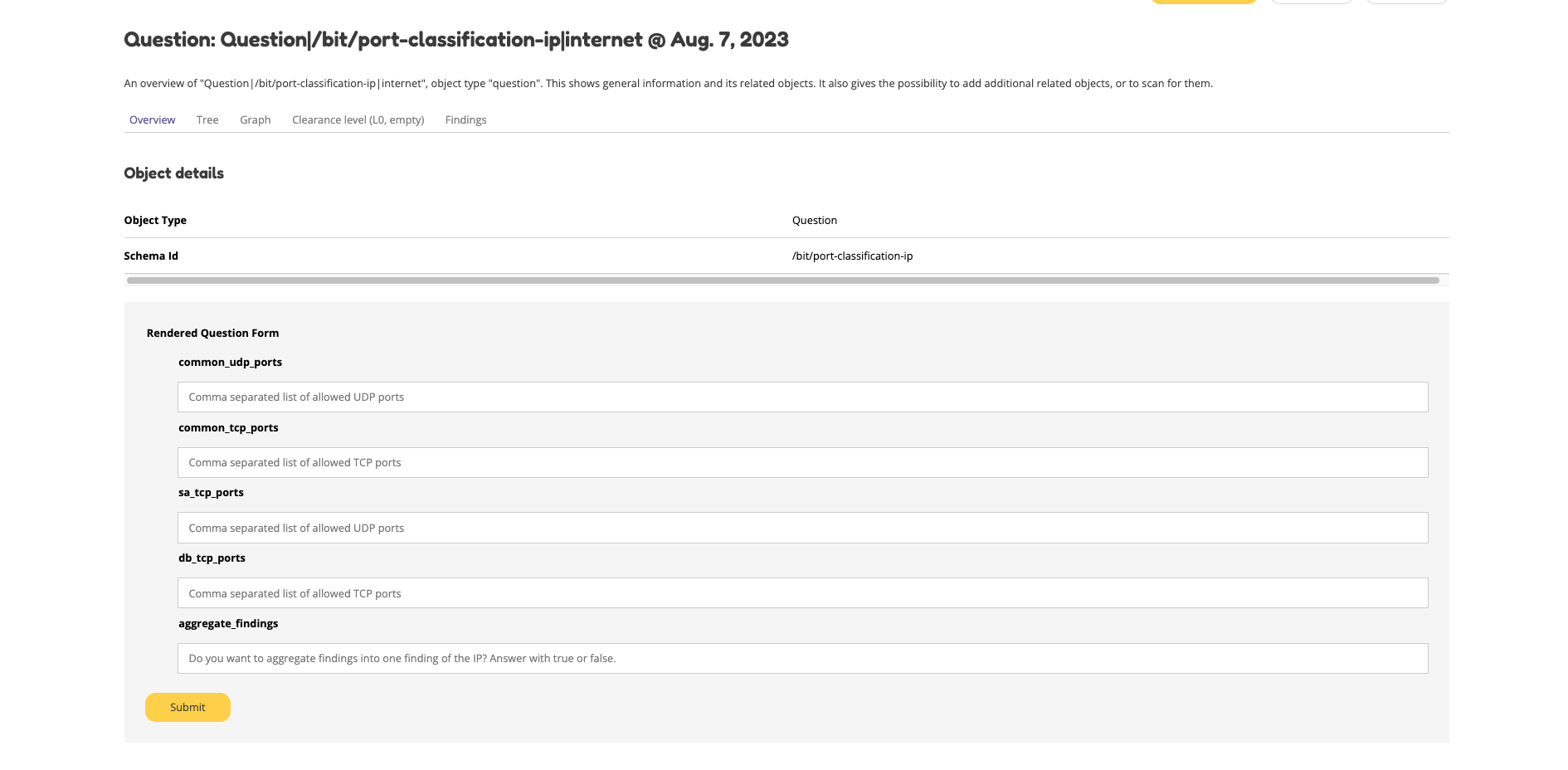

Question object

Configurable bits require a place where the configuration is stored. It needs to be tracable, as the configuration is important when judging the results of a scan. The solution is to store the config in the graph.

When a relevant object is created, a configurable bit throws a question object at the user. This question can be answered with a json file or through the webinterface. The configuration of the bit is then stored as an object in the graph.

My first question object

Under ‘Objects’, create a network object called ‘internet’. Automagically a question object will be created. You will be able to find it in the objects list. If you already have a lot of objects, filter it using the ‘question’ objecttype.

The question object allows you to customize the relevant parameters. At the time of writing, the only configurable bit is IPport. This allows you to change the allowed ports on a host.

Open the question object, answer the questions and store the policy of your organization. Besides the allowed and not allowed ports, this bit also has the option to aggregate findings directly.

The IPport question object has five fields:

Allowed:

common udp ports

common tcp ports

Not allowed:

sa ports (sysadmin)

db ports (database)

Findings:

aggregate findings

After adding the relevant information, your question object will be stored and applied directly. It can be changed or added through the webinterface.

What happens in the background?

The question object is more than just a tool to allow or disallow ports, it is the framework for future development on configurations. A configurable ruleset is a basic requirement for a system like OpenKAT and we expect it to evolve.

The dataflow of the question object works as per this diagram:

After the relevant object has been created, within the normal flow of OpenKAT a question object will be created. The advantage of this is to store all relevant data in the graph itself, which allows for future development.

Advantages and outlook

Storing the configs in the graph is a bit more complex than just using a config file which can be edited and reloaded at will. The advantage of storing the configuration in the graph is that it allows the user to see from when to when a certain configuration was used within OpenKAT.

In the future, one goal is to have ‘profiles’ with a specific configuration that can be deployed automagically. Another wish is to add scope to these question objects, relating them to specific objects or for instance network segments.

Add Boefjes

There are a number of ways to add your new boefje to OpenKAT.

Put your boefje in the local folder with the other boefjes

Do a commit of your code, after review it can be included

Add an image server in the KAT catalog config file

*

* If you want to add an image server, join the ongoing project to standardize and describe it. The idea is to add an image server in the KAT catalog config file that has artifacts from your boefjes and normalizers as outputted by the GitHub CI.